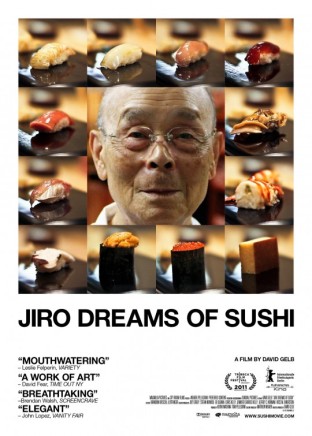

Documentaries about food have seldom been so engaging and uplifting. Jiro Dreams of Sushi(2011) follows the operations of a miniscule sushi restaurant in Tokyo which happens to be regarded as producing the best sushi in the world. Jiro Ono is an octogenarian who has been honing his craft of sushi-making for most of his life. His fastidiousness, indefatigable work ethic and a passion for sushi are highlighted throughout the film with quiet care. The relationship between Jiro’s sons (also sushi chefs) and himself brings an element of drama that is unexpected from a story about fish. This documentary is a lovely illustration of a passionate senior and his gift to the world of meticulously-crafted sushi.

Documentaries about food have seldom been so engaging and uplifting. Jiro Dreams of Sushi(2011) follows the operations of a miniscule sushi restaurant in Tokyo which happens to be regarded as producing the best sushi in the world. Jiro Ono is an octogenarian who has been honing his craft of sushi-making for most of his life. His fastidiousness, indefatigable work ethic and a passion for sushi are highlighted throughout the film with quiet care. The relationship between Jiro’s sons (also sushi chefs) and himself brings an element of drama that is unexpected from a story about fish. This documentary is a lovely illustration of a passionate senior and his gift to the world of meticulously-crafted sushi.

Monthly Archives: August 2013

Happy Friday: Treme returns to HBO…eventually

It has been announced that David Simon’s Treme will return to HBO in December 2013 for it’s final season. Only five episodes of the New Orleans- after-Katrina program will be aired. Read more here to find out the particulars. Since the return has been pushed back again I urge you to borrow the previous seasons at your local library in the meantime and catch up, if you haven’t watched it yet. I have a feeling that not many have watched this show, as I usually get blank stares when I mention it or people say, “It’s boring”. Admittedly, the show does not have the swiftest narrative, but it pays off if you stick with it. The musical performances alone are enough to keep you watching; fantastic stuff. The cast is also exceptional; John Goodman, Khandi Alexander, Wendell Pierce, Clarke Peters, Steve Zahn and my personal favorite Phyllis Montana LeBlanc. Ms. LeBlanc appeared in Spike Lee’s documentary When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts and told her story of the catastrophe of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. This is her first acting job and she knocks it out of the park. Treme is a little fish that swims in the sea of flash that dominates the serious television world. But it is the prettiest of them all.

It has been announced that David Simon’s Treme will return to HBO in December 2013 for it’s final season. Only five episodes of the New Orleans- after-Katrina program will be aired. Read more here to find out the particulars. Since the return has been pushed back again I urge you to borrow the previous seasons at your local library in the meantime and catch up, if you haven’t watched it yet. I have a feeling that not many have watched this show, as I usually get blank stares when I mention it or people say, “It’s boring”. Admittedly, the show does not have the swiftest narrative, but it pays off if you stick with it. The musical performances alone are enough to keep you watching; fantastic stuff. The cast is also exceptional; John Goodman, Khandi Alexander, Wendell Pierce, Clarke Peters, Steve Zahn and my personal favorite Phyllis Montana LeBlanc. Ms. LeBlanc appeared in Spike Lee’s documentary When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts and told her story of the catastrophe of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. This is her first acting job and she knocks it out of the park. Treme is a little fish that swims in the sea of flash that dominates the serious television world. But it is the prettiest of them all.

Old (Film) School: Musicals

Originally written on October 24, 2002

In recent years, there has been a slight resurgence in musical films. The musical genre has gone through many changes throughout film history. It initially started as a grand spectacle not tied to any narrative. Later on, the musical was relegated to specific sequences throughout a film that helped to advance the narrative. Recently, three films have used musical conventions to varying degrees of effectiveness. The overly ambitious Moulin Rouge! used contemporary popular music in a tradition musical narrative. In Dancer in the Dark musical conventions were used, but in a massive repudiation of all that was known of musicals. In Hedwig and the Angry Inch conventions of traditional musicals are blended with a shocking story. The latter two films will be discussed for their ambitious and inventive use and redirection of musical conventions.

Though there are general rules of the musical form, much has changed over time in these films. Early in cinematic history, musicals were not part of a narrative. The musical was just a grand spectacle with popular music of the day. In 1952, the release of Singin’ in the Rain became a landmark film musical. The superb singing and dancing of the stars upped the ante of musicals. This film also used the convention of spontaneous singing. Though people do not generally start singing about their emotions in real life, in a musical this is seen as normal. In the case of Singin’ in the Rain the film follows actors who are meant to sing. Therefore their singing is not seen as so weird(Berliner, 2).

In 1960’s brought forth two notable musicals that are now classics. In 1961, West Side Story by Leonard Bernstein, presented a modern retelling of Romeo and Juliet. This film used spontaneous singing and masterful choreography to tell the story of the doomed lovers. This musical is a repudiation because it is not a happy story and leaves audiences running for the Kleenex. In 1964, My Fair Lady arrived on the screen. This is a lighthearted retelling of Pygmalion, which starred Audrey Hepburn. This musical also used spontaneous song as a narrative device, but has a happy ending. In this way, My Fair Lady is a repetition of musical form.

In the 1970’s, musicals became more serious, more adult, so to speak, then previously. These musicals were not often appropriate for children, for they dealt with subject matter in a much more realistic manner. In 1972, Cabaret, starring Liza Minelli and Joel Grey, debuted. The film takes place in the Weimar Republic right before the Nazi takeover. This musical is an amplification because the musical sequences take place at the Kit Kat Club and are sometimes interspersed with scenes from “real” life. The singing only takes place because Sally Bowles is a singer at the club and the songs reflect her feelings and those of the Germans, in general. Another amplification is the character of the Master of Ceremonies, played by Joel Grey, who is an omniscient narrator who does not exist outside the club. He somehow knows the inner workings of Sally’s psyche and also embodies the distrust of all people towards the Nazis.

In 1973, Andrew Lloyd Weber’s musical Jesus Christ Superstar was adapted for screen. This musical is a repudiation of both the musical genre and the subject matter. This film portrays Jesus as not only the messiah, but as a rock star. Judas is both annoyed with Jesus’ flagrant disregard for authority but also his seeming need for the adulation of his followers. The traditional musical sequences take place on location, in Israel. The dancers, though obviously trained, all look like ragged hippies. The final sequences of the film are not joyful, but disturbing. Jesus is crucified while a frightening montage of portraits of the crucifixion are shown on screen. Then Jesus (possibly) goes to heaven and is sung to by the reviled Judas. In the end, a somber melody is played while the cast rides off into the desert, without Jesus on the bus. This scene is chilling and shows the lengths that director Jewison went to repudiate the musical form.

In present cinema, the musical is fairly rare. That is why Dancer in the Dark is such an interesting example of a musical. One does not even know that this film is a musical until about forty minutes into the film. Up to this point in the film non-diegetic music does not exist. The only music comes from the rehearsals Selma participates in for a community production of The Sound of Music.

When the film turns into a musical, the audience is caught off guard. This shift is a massive repudiation on the part of the director, von Trier. The musical sequences are filmed in brilliant color and transport Selma into a fantasy world of the musical. This is her only escape from her awful life of drudgery and blindness.

The musical scenes themselves are repudiations. In these scenes, Selma’s change of reality is so drastic, that they seem fairly magical. Right after she brutally murders Bill, he is dancing with her and forgives her. So does his wife and her son Gene. In reality, these people would never have forgiven Selma, but her musical fantasies help her cope with the stress of her doomed existence.

The scene when Selma is in isolation at the jail is a repudiation of musical conventions. In this scene she does not sing her own original tune. She sings My Favorite Things from The Sound of Music to distract her from the silence of the jail. This scene is disturbing because the audience can see that the artifice of musical-as-coping-mechanism is not working any more. The use of music from another prominent musical is also a strong repudiation.

The final sequence of Dancer is most disturbing and uses the convention of spontaneous song, without launching into a fantasy world. Selma is being hanged for the murder of Bill, and is apoplectic over her demise. When Kathy informs her that Gene has gotten the operation and will see, Selma’s attitude changes drastically. A calm washes over her face and she sings a haunting song about this “Not being the last song.” This is a reference to her distaste of the end of musicals when you see the crane shot that goes out the roof and you know the film is over. Unfortunately, for Selma, she is hanged and we see the camera crane up in just the motion she described. With her death and this camera movement, we know the film is over, for the audience and also Selma.

The repudiations in this film are used to show the fallacy of musicals. Lars von Trier was aiming to show that musicals are quite fanciful and untrue. Selma came to America because of musicals and the hope that everything there would be as wonderful as in a musical. She unfortunately found that in America money and status mean more to people than hard work for the medical care of a child. This film is truly an indictment of American culture and the void it creates in people’s hearts.

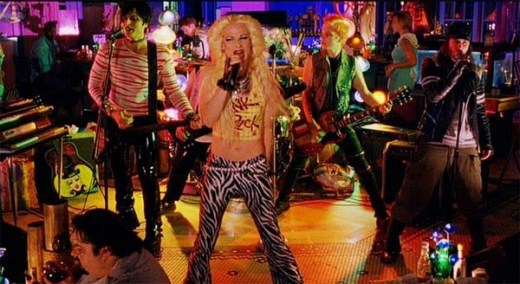

Another recent musical that is a repudiation in content is Hedwig and the Angry Inch. This film follows the exploits of the transgendered rock singer Hedwig. Hedwig began life as a man and to escape Communist East Berlin, got a sex change operation to become a woman. While in America, Hedwig is left by her husband and then starts a musical career. This is when she meets with her muse, Tommy Gnosis, who breaks her heart and steals her songs.

The context in which musical sequences are used in this film are mainly performance. The songs that the band plays are of a narrative mode. We learn of Hedwig’s entire life through the songs. Wig in a Box is one of the performances that most closely mimics the style of traditional musicals (Seminara, 3). Hedwig has just been left by her husband and then her band enters her house as a grand sequence ensues. Her motor-home becomes a grand stage and the use of a sweeping crane shot in the end signals a throwback to old musicals.

The story told in Hedwig is not of a usual musical variety. Very few, if any, musicals have centered on a transgendered subject. The only film to come close to this was Victor/Victoria from 1982. This film dealt with gayness in a joking and gay (no pun intended) way. Though the subject was unusual for a musical, Victor/Victoria was mainstream because Julie Andrews played the lead role. In Hedwig, the subject, though amusing at times, is also consciously serious.

This film is important because it offers a transgendered character who is sympathetic. Though Hedwig is often hassled for being transgendered, it is heartening to see that she will not apologize for herself. Hedwig is reminiscent of old time women performers who were oh-so-cool. When speaking of her past attempts at singing in public (though really just in front of his mother) she says, “I had tried singing once and they threw tomatoes so after the show I had a nice salad.” Or when the young Tommy Speck asks her if she had accepted Jesus Christ as her personal savior she replied, ” No, but I love his work.” These zany one-liners illustrate that Hedwig is a vibrant woman who can take anything that is thrown at her and make it entertaining and insightful.

The examination of the musical genre finds many discrepancies within the genre. The conventions of spontaneous singing and the use of song as a narrative advancing device are commonly present. The use of song as emotional expression is usual, especially in Dancer in the Dark. Yet these few modes do not seem to correlate to a common ground on what musicals are.

The stories of the musicals examined are incredibly diverse. They run the gamut from biblical drama to the suffering of poor, blind Selma. The main characteristic of musicals, then seems to be, not the repetitions, repudiations, or amplifications of the genre, but the strong characters presented in each. When speaking of melodrama, which can also be compared to musicals, Noel Carrol stated,

“One important, recurring motif here is that the victim of melodramatic misfortune often accepts her suffering in order to benefit another, often at the expense of her own personal desires and interests. Sometimes, in fact the character’s misfortune is a result of the sacrifices she has made on behalf of others (Plantinga, 36).”

Most of the films examined follow this argument. Selma is no less dying for the sins of Bill, as Jesus is dying for the sins of the Israelites. Hedwig must endure constant identity crisis because of the choices that were made for her. This comparison can be made with most musicals, and shows the real link between them. Strong lead characters who must rise above diversity to meet their goals are the mainstay of musicals. The conventions of the musical lend themselves to telling stories about the most uncommon, yet interesting people whose stories would not be as vibrant without the musical mode.

References

Aloi, P. (2001) Little Seen, Long Remembered. Art New England, 22 no 6 3, 83 0/N. Retrieved on October 17,2002, from the Wilson Web database.

Arroyo, J. (2000) How do you solve a problem like von Trier? Sight & Sound, ns10 no 9 14- 16 S. Retrieved on October 17, 2002, from the Wilson Web database.

Berlinger, T. (2002) The Sounds of Silence: Songs on Hollywood Films since the 1960’s. Style, 36 no119-35. Retrieved on October 17, 2002, from the Wilson Web database.

Plantinga, C. and Smith, G.(Eds.) (1999). Passionate Views: Film, Cognition, and Emotion.Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Seminara, 0.(2001) Music (Wo)Man. American Cinematographer, 82 no 7 20-7. Retrieved on October 17, 2002, from the Wilson Web database.